Bystander Effect in the Mainstream (insights and reflections)

- jamie03066

- May 9, 2022

- 7 min read

Back in 2013

Hinnerup Karate

in Denmark invited me to teach my full "When Parents Aren't Around" (young person's self-protection) course (10 hours) in addition to some "Vagabond Warriors" work. Whilst teaching the children's self-protection, I addressed the bystander effect as a single topic. This was an area in self-protection that just wasn't being recognised let alone taught much. We had touched upon it when teaching in London for Mo Teague's Hard Target, but outside of it challenging the idea that "there is safety in numbers" many of us just weren't addressing the issues surrounding the matter.

For my part, I did what most self-respecting and self-righteous self-protection teachers do: I bemoaned the lack of education in the self-protection teaching world. Spending way too much time on social media, I noticed respected, if rather crusty, self-protection and martial arts teachers brandishing their confirmation biases about the fate of today's society. The people of today, according to them, were either too soft, too cowardly, too passive or less caring than in previous times.

It became part of my "The Boxing Kangaroo and the Law of Instrument" (revised, edited and collected in "Wrong Fu") and remains one of many topics I label "given only lip service at best in most self-protection classes". By including it in my course for the first time when I taught in Denmark, I really thought I was doing enough (more than most) to bring the matter to the attention of those I was serving. However, this episode served to be yet another time when the children I was teaching put me to the test and made me think more deeply about the material I was covering. One young boy asked the reasonable (yet never asked before) question "Well, how do we get people to help us?" Within the context of the lesson, he was asking "How do we defeat bystander effect?"

To be fair to the material of course, since I developed the predator versus prey game in my club it became evident that those taking on the role of prey had a chance of surviving longer should they work together against the predators. This immediately helped me answer the question on the day, but it made me think more about expanding upon this area. The 10-80-10 rule regarding mass reactions to a mass crisis situation was a helpful part of this education (

), but I also needed to delve back into my primary education. For those of you playing Clubb Chimera Bingo, this is the part where I reference my circus background. Although I officially left life living on a travelling circus when I was seven years old, I never left the actual culture. However, a key rule drummed into us from an early age was to "not just stand around". We were always given roles to do during a crisis situation - which could vary considerably when one is on the road, in a totally foreign environment and being around hazardous machinery, animals and sometimes people. Stories of people who froze during a dangerous situation and also how groups were motivated to aid in a crisis were regular part of conversations held in crowded wagons or around impromptu barbecue parties on the shows. The information I gleaned from these times was then supported by what small numbers of studies had been done when individuals had defeated the bystander effect. In simple terms, bystander effect can be defeated by trained individuals taking on the role of leader and issuing instructions. This was the information I passed on in the teenage exclusive edition of my "When Parents Aren't Around" courses I taught around the Oxfordshire region during the mid-2010s.

In 2020 and '21 I taught soft skills exclusive webinars and lessons where I could spend more time discussing the bystander effect in detail. Since then, bookings of my course with such clubs as Vijay Pathak's Forest School of Karate and my termly lessons at Kingham Hill School have continued to improve upon how defeating bystander effect can be taught in a practical way.

In 2022 I was one of the fortunate number of first generation provisional teachers who were trained at Joe Saunders 3-day instructor course in Managing Violence. I was happy to see that amongst the extensive amount of soft skills covered during this course, the bystander effect was addressed in detail. Finally, modern self-protection teachers were bringing this incredibly important area into their education and services.

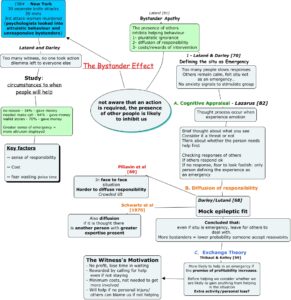

This isn't to say that the bystander effect doesn't have its detractors. In fact, scientific studies as recent as 2019 have offered evidence that might debunk the theory once a for all. My thanks to self-protection and martial arts teacher Dr John Titchen who responded to an earlier version of this article and pointed me in the right direction. Gretchen Carlson should also have been given credit and I should have mentally logged the episode of her excellent show "The Martial Journeys Podcast" where also did a great job of critically deconstructing bystander effect history. The origin of the theory can be traced back to the Kitty Genovese case of 1964. Genovese was sexually assaulted and murdered outside of her apartment. The story was first reported in the New York Times describing how the 28 year-old bartender had been killed whilst 37 bystanders did nothing. Such a cast became the basis for social psychologists,Bibb Latane and John Darley to research the reasons behind this action and to publish it in their 1970 book, "The Unresponsive Bystander". The bystander effect was born, but it wasn't without scientific scrutiny. Various studies were conducted since Latane and Darley's book further confirming their theory up until 1981. In 2011 "The bystander-effect: A meta-analytic review on bystander intervention in dangerous and non-dangerous emergencies" was published for the American Psychological Association to update the reviews and to offer a meta-analysis on the subject. This particular study highlighted reasoning behind why people broke bystander effect, which did not contradict the theory. When an individual felt they had sole responsibility they were more likely to act. This is more likely when there are less people present.

However, not long after the tragedy of Kitty Genovese, the same newspaper who had first broke the news revealed the story had been exaggerated. Firstly, there had not been as many witnesses as first had been stated. Secondly, some of the supposed bystanders had called the police. This report did not debunk bystander effect, but it inspired others to consider that it might be more complicated than first thought. In 2008 Daniel Stalder's analysis of previous studies concluded that bystander effect was real but that larger group size increased the chances of someone acting. This was then supported by Richard Philpot's article which he reported on a study he conducted with four other psychologists where they compared CCTV footage of conflicts taken from three countries, Netherlands, South Africa and the UK. Philpot went a stage further by saying that his largest systematic study of bystander behaviour reveals it is actually more likely for a bystander to act especially if there are greater numbers.

This latest study is more reassuring than what we have assumed with the bystander effect. I have read other articles that try to completely dismiss the theory under the same cynicism I saw being exhibited by those who believed bystanders were a product of our apathetic and morally degraded times. However, those who generally tried to explain the bystander effect were the complete opposite to the pessimists. They tried to explain how diffusion of responsibility and the "volunteer's dilemma", the bystander effect described by game theorists, were more a result of natural human herd activity. Regardless of this point, there is still many instances caught on film that demonstrate what appears to be bystanders watching on or ignoring a person in trouble.

You only have to do a cursory search of videos to see various television shows that set up tests with groups of volunteers:

Others show actors planted amongst the general public in a busy place to see how long it took before people intervened.

One such video was specifically used to show how a child might be abducted in broad daylight with the young actor screaming "Help! You're not my Dad".

Looking through the lens of the new studies, it is interesting to consider not whether or a Good Samaritan stepped in but how long it took before they did act. Who were the people who acted? What motivated them or gave them confidence possibly lacking in others? This is not a scientific theory rather pure speculation on my behalf, but perhaps the 10 - 80 -10 rule might lend something. Usually we discuss the 10 - 80 - 10 with regard to a crisis occurring to a group of people, such as if the passenger plane were to go down. In such cases, typically 10 percent of the passengers panic, 10 percent default down to their level of training or experience, and the remaining 80 await orders. Maybe it might be considered as we explore the bystander effect in more depth as

demonstrates. Lately, the bystander effect in the workplace is being spotlighted. The article offers some practical advice on breaking the bystander effect and how it can reduce the impact of bullying. Hopefully it will yield more data for us to formulate better self-protection plans. However, for the time being the advice to train students leadership skills in a crisis and to be able to recruit new allies still stands.

My thanks to Jan Drachmann and Flemming Andersen (as well as the unnamed young man who asked the question) for booking me to teach in Denmark and helping me to further improve the services I deliver; Mo Teague for entrusting me to teach his excellent self-protection course in 2010; Al Cain for being the first self-protection teacher I noticed to publicly address bystander effect in a class; Lee Mullan for hosting me back in early 2019 where I began piloting the improved version of the predator versus prey game.

https://clubbchimera.com/courses/

Comments